|

Forestry and the Timber Industry

1. General Overview of the Forestry Situation

The reasons for this sharp decrease of forested land are to be found first of all in the replacement of the peasants' right of usufruct* with their right to personal ownership of much smaller woodlots assigned to them; second, in the extensive reorganization of wooded areas, in the course of which the forest was usually clear-cut; as well as, third, in the dire financial straits of the major woodland owners, whose debts forced them to

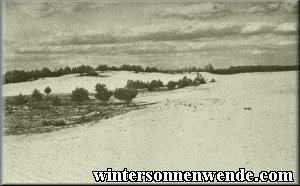

The diagram, representing the area within a 60 km. radius of Warsaw, shows clearly how deforestation has progressed over the years. The map shows that in 1863 a very large portion of the overall area was still forested. By 1935, however, these wooded areas had dwindled dramatically. Unlike in the Reich, there are very few community woodlands in the area of the former Polish Republic. The absence of this source of income is often partly responsible for the financial weakness of the communities. Peasant-owned woodlots are generally tiny – usually the direct result of the cancellation of the right of usufruct.

a. Location, Climate and Soil The District of Warsaw is located almost entirely in the Vistula Basin; its elevation ranges from 75 m. (at Sochaczew) to 220 m. (between Wengrow and Kaluszyn) above sea level. Temperatures

Annual precipitation is fairly low, ranging from 600 to 700 mm. in the southern parts of the District and from 500 to 600 mm. in the north. Less than 500 mm. have even been measured in the Narew lowlands. Beech and silver fir will not grow in areas with less than 600 mm. of precipitation, but the remaining kinds of trees still grow satisfactorily. The favorable climatic conditions are due to the prevailing westerly winds. The easterlies, on the other hand, bring with them extremes of temperature, drought, night frosts, and early and late seasonal frosts, which are no less damaging to forestry than the spring droughts, which are usually of long duration.

b. Condition of the Woodlands On Assumption Into German Care

The thoughtless overconsumption of mature trees from the privately owned woodlots had already been documented in the mid-1800s, and the overexploitation of this resource has progressed further since 1918. Financial difficulties, overspending, fear of property nationalization, and the redistribution of land among the peasants were some of the reasons for this trend. The common practice of large-scale clear-cutting, as well as the inadequate training of forestry personnel, has also contributed to the worsening of the situation. Peasant woodlots were never accorded any proper forest management. Forest grazing and straw-substitute collection practices have done much harm. Great damage was also done by the harsh winters of 1928–29 and 1939–40, particularly to pine and beech stands. Similarly, the first world war and the Polish Campaign of 1939 have also inflicted many wounds on the forests, especially in those areas where the battles took place. But most of all, the widespread practice of lumber theft, primarily near cities and towns, has served to considerably thin the stands and even to decimate the overall forest resources in some localities.

c. The Situation Regarding Wild Game Wild game has been only moderately abundant in the District of Warsaw for decades. Even if some private owners of woodlots have devoted much attention to the care of small game, most game and hunting regions in the District are impoverished compared to their German counterparts. Rampant poaching and especially the severe winter of 1939–40 have greatly compromised the game supply. The elk has disappeared completely. The number of red deer as well has decreased to about 10 animals; the last royal stag (a 16-pointer) was killed in 1916 on the Ostrow moor; the dressed carcass is said to have weighed 257 kg. Wild boars can be found in larger, contiguous forested areas. The last fallow deer fell victim to the Polish Campaign. Roe deer are everywhere, albeit in very small numbers. On occasion, royal stags with antlers weighing more than 500 g. have been killed. Their body weight is considerably greater than that of roe deer in the Reich, the difference in the dressed carcasses being 40 to 50 lb. on average. Hares are also to be found everywhere. The best hunting regions for hares are in the western counties, where the soil is fertile. Rabbits are most common west of the Vistula. Foxes are common, but badgers have decreased in number, as have otters. Stone and pine martens, polecats** and both species of weasel are still to be found. Wolves are restricted to their old ranges east of the River Bug; the beaver and lynx are extinct. Among the game birds, black grouse are still strongly represented, but the capercaillie (wood grouse) has vanished. The partridge population was decimated by the harsh winter of 1939–40. Pheasants can only be found in the most carefully tended game and hunting regions. The great bustard was last spotted in 1939. Ring doves, turtledoves and rock doves are common. Marshlands, rivers, lakes and ponds are populated by waders and waterfowl; there are all kinds of ducks, the common lapwings, gulls, diving birds, bitterns, curlews, snipes and coots. Even the rare fighting cock can sometimes be seen. The black stork is still represented in the avifauna, and ravens are also not uncommon. However, no eagle owls have been observed to date, and the same goes for the various species of eagles.

2. Reconstruction and Development of Forestry and the Timber Industry When the General Government was established in autumn of 1939 the German Forestry Administration took over the management and care of the forests and wild game as well as the reconstruction and development of all operations pertaining to forestry and logging within the boundaries of the General Government.

a. Administrative Structure The Division of Forestry began its work by first dividing the District of Warsaw into eight large forest regions to serve as so-called Forestry Inspection Regions; their number was later reduced to seven. The area of these Inspection Regions averaged 25,000 to 30,000 hectares. Forestry Inspectorates were placed under the leadership of a German Forestry Commissioner*** who had from one to three forestry officials assigned to him, depending on how much work the Inspection Region in question demanded. The reorganization of forest management in the General Government also entailed the completely new spatial division of the District of Warsaw. Inspectorates were grouped into four large Supervisory Departments with headquarters in Ostrow, Skierniewice, Warsaw and Sokolow. Each Supervisory Department is responsible for the Head Forest Wardens (an office also newly created) in its region. On average, a Head Forest Warden has charge of 5,000 to 8,000 hectares of woodlands, regardless of their ownership, and the personnel of each such office is made up exclusively of former Polish forestry officials. The further regrouping into two Supervisory Departments, Warsaw East and West, was carried out in autumn of 1941.

b. The Logging Industry After German forestry authorities had taken charge of the forests, the whole of the woodlands in the occupied part of Poland had to be drawn on as extensively and comprehensively as possible to provide the vast quantities of lumber required for an ultimate German victory. It was important that logging should begin right away. Mine support timbering, firewood, construction lumber, and wood for many other uses was urgently needed in the Reich proper. As well, 10% of the coniferous trunk wood that was cut was to be used for reconstruction purposes in the occupied Polish territory. Beyond that, the inadequate supply of coal necessitated extensive cutting of firewood for the people, and the extremely high consumption of firewood in the former Polish Republic suggested that it might be possible to increase the amounts of utilizable timber and especially mine support timbering and the like at the expense of the firewood supply. It soon became clear from the Wehrmacht's ever-increasing need for coniferous trunk wood that more of this kind of lumber would have to be cut and supplied to the Wehrmacht on short order than had initially been expected. This required the mustering-up of all available forces for the clear-cutting of timber stands in close proximity to transport facilities and particularly in locations from which the transport of timber would still be possible even after the spring thaw. These measures could not have been successfully taken without the greatest possible contribution by all German officials involved. Despite great difficulties, almost the whole of the required timber was cut in 1940. The unusually long and bitter winter, the insufficient diet and attire of the Polish lumberjacks, and the inadequate tools were the main problems; on the whole, however, the achievements of 1940 may be considered a success. No more than the normal year's worth of timber was to be cut in 1941. But the course of political relations with Soviet Russia once more created a huge demand for lumber, which again had to be supplied on short notice. In addition, large orders for construction lumber were placed for the Organization Todt.**** And finally, large quantities of lumber had to be provided for the Division of Food and Agriculture's accelerated reconstruction of destroyed farm buildings and warehouses and other repairs and improvements. All these demands did not allow for the setting of a logging limit – the required quantities simply had to be cut. At the same time, the difficulties of logging and the provision of the timber had not decreased. Nevertheless, all demands were filled and all consumers adequately supplied. Given the lack of availability of coal, the firewood that had been cut in the District to supply the people and the industrial establishments was insufficient to meet the unusually high demand, and considerable quantities of extra fuel had to be imported from the Districts of Lublin and Radom. Aside from a few thousand cords of wood which were exported to the Reich, the entire supply of coniferous trunk wood of both years was processed in sawmills within the District itself. Mine support, timbering and the like was placed at the disposal of the Reich. In the Reich proper, the transport of lumber is the sole responsibility of the buyer. In the General Government it was soon found that transporting the wood could not be left entirely up to the buyers as these could not provide the vehicles necessary for such an endeavor. The Forestry Supervision Departments therefore had to take this matter into their own hands as well to ensure that the lumber would be processed on schedule. The paths which had been cleared through the forests during the world war and which still existed were brought back into use. There were two such paths, 34 km. long altogether. The horse-drawn "panje" carts which were still available in adequate numbers even as late as 1939–40 were best suited to the transport of lumber by virtue of their durability and ease of handling. Later, however, the levying of horses for the Wehrmacht as well as the needs of the road construction departments greatly decreased the available number of horses, and finally, in November of 1940, the process of supplying potatoes to Warsaw brought lumbering activities to an almost complete standstill as the peasants needed their horse-carts to transport their produce to the city. In the spring of 1941 further thousands of teams were levied which practically immobilized the remaining lumber transports, particularly in the eastern county precincts. That the cut timber was transported for processing on schedule despite all these difficulties is a great achievement on the part of the German Forestry Commission.

c. Forestry The concerns of forest care and maintenance initially had to take a back seat to the foremost responsibility of the Forestry Commission: the cutting and supply of the required quantities of lumber. This has precluded any fundamental improvement in the forest situation. In filling the enormous demand for wood it was often necessary to gear logging operations to specific kinds of trees in locations readily accessible for transportation purposes, but most short-term orders were best filled by retaining the clear-cutting method, preferably of those kinds of trees that were most convenient for transport. Even though every effort was made to include as many unhealthy trees as possible – particularly those infested with fungi, or those that were damaged during the war –, the District's reserves of mature and old wood did nevertheless dwindle even more in the last few years. It was especially difficult to ensure that the seeds and seedlings required for 1940 would be available; harvests had been poor, and neither seeds nor seedlings were available for import from the Reich. As a result only 1,200 hectares could be planted. In 1941 the total area was a little less than twice that much. A great deal of catching-up will need to be done in this respect in future years. An assessment of land in need of cultivation has served as the basis for plans for a large-scale reforestation program. The establishment of large tree nurseries has already begun, so that the areas earmarked for reforestation can in time be planted with locally grown seedlings. Of the various forest by-products, tree resin is of particular importance to the German war economy. For this reason it was an important task in 1939 to secure existent resin supplies. Resin was frequently stored in barrels in the cellars of the woodland estates. An estimated 5,000 kg. was collected. The collection of tree resin was resumed in spring of 1940.

In 1941, on the other hand, the peat-cutting outfits had produced 20,000 tons of peat by September 1st. The yield from smaller sites (less than 2 hectares) may be estimated at 10,000 tons, so that production totals some 30,000 tons. 50,000 tons are expected for 1942. All work in the forests has been made more difficult by the initially total absence of any sort of forest patrol; such an enforcement system is still incomplete today. Due to extremely liberal laws as well as the leniency of the courts in applying them, lumber theft and related offenses had taken on incredible proportions in Poland. The first step towards counteracting this situation was to arm the existing and in some cases quite willing Polish forest law enforcement personnel. Hunting rifles that had been confiscated by the German police, or else imported from the Reich, were supplied for this purpose. The Forest Patrol of the Reich Forest Commissioner thus began operations in early May of 1940. Its functions were initially restricted to monitoring timber transport and putting a stop to lumber theft. The smuggling of wood into Warsaw has been firmly brought under control, resulting in the recovery of considerable amounts of firewood which have been sold at reasonable cost through a mediating lumber firm. Smaller patrol units have also conducted searches of villages and towns to recover stolen lumber. Above and beyond their function in facilitating and monitoring the transport of lumber, patrol members have also been active as forest and wild game rangers. All measures have had sweeping success.

d. Wild Game The wild game population suffered greatly from the war and its consequences as well as from the severe winter of 1939–40. In autumn of 1939 the first concern was to preserve the still-existing wild game population as much as possible. For this reason laws for the permanent protection of endangered species were passed, pertaining to, for example, roe deer, pheasants, and partridge females. The latter are still under protection today. Aside from hares and ducks, the game populations of roe deer, wild boars and pheasants are rather small and still require comprehensive protection and care. Authorities of the various game and hunting regions see to the feeding of game animals, but more remains to be done. The same also goes for the raising and care of pheasants. An improvement in the game population is much to be desired. It may be expected that the introduction of the Reich Game Laws will lay the necessary foundations towards this end. If the landowners do what is necessary for the care and preservation of the various kinds of game on their land, by the introduction of healthy new individuals if necessary, then game populations in the General Government may soon be a match for those in the Reich. The District as a whole is divided into 370 game and hunting regions which are assigned, for hunting purposes, to Wehrmacht and SS authorities or to civilian hunters and forestry authorities. Property owners are financially compensated for kills made on their land. The game which is killed is provided at prescribed cost to the inns of the Wehrmacht and the civil administration, as well as to hospitals.

3. Future Responsibilities of the German Forestry Commission Bearing in mind that the District of Warsaw is a sparsely forested area with a great demand for wood, that the forests contain only few mature and old trees ready to be cut, and that private woodlots in particular are unsatisfactorily timbered, the chief responsibilities in the future must be to increase the present-day forest areas as well as to improve the overall condition of the forests. To attain this goal, clear-cutting is to be restricted to absolutely necessary exceptions in order to prevent the creation of further areas requiring complete reforestation. In the main, increasing forest quantity and quality involves the reforestation of land not suited for agricultural cultivation, restocking clear-cut areas, touching up old woodlands, and the reforestation of the numerous barrens. To achieve these goals it will be necessary to improve the methods of cultivation commonly used in this field, to obtain high-quality seed, and to grow the seedling plants required. Pastures must be fenced in where grazing is a hazard for reforestation programs. Professional training of the Polish forestry officials will be indispensable, and is already being provided. The constant clearing of forests for conversion to agricultural land must be prohibited, since the forests still in existence today stand on forest soil frequently not suited to non-forest vegetation anyway: in the past decades, wooded areas cleared for agricultural purposes were in many cases found to be useless for farming. If the conversion of woodland is not stopped the District will become a steppe, with concomitant disadvantages for the soil, climate and social welfare of this region. Another task for the future is to reduce the need for wood. With its small proportion of forested land, and its consumption of wood by far exceeding German standards, the District of Warsaw is a pronounced wood-deficit region. That the former Polish Republic was in fact a timber-exporting nation until the time of its take-over by the Germans was an economic role which was very much to the detriment of its forests, which had slowly but surely approached irreversible destruction. In light of how rapidly this natural resource has been used up in the last 20 years, it is clear that there was no proper forest management whatsoever. The rural as well as the urban people use far more wood than their counterparts in Germany. One of the reasons for this is that firewood is virtually the only source of indoor heating; coal is rarely if ever used in the country. Further, houses are almost always made of wood, both in the villages and the towns. Enormous quantities of wood are thus consumed and the forests cannot permanently keep up with such demand. The consumption of wood must be cut back as soon as the trade situation has returned to normal. Most regions of the General Government are not exporters of wood, but the District of Warsaw is a particularly pronounced importer. Wood must be imported, not exported; but at the same time, construction methods must be shifted from wood to stone and heating methods from firewood to coal. To achieve such changes, forestry must be given the support of systematic propaganda and education. And finally, one of the most pressing future tasks is the creation of forest laws which will provide the required legal framework for the great responsibilities involved in the quantitative increase and qualitative improvement of the forests. Important aspects require speedy legal control, particularly the management and care of the forests; the union of peasant woodland owners in forestry co-operatives; the reforestation of barrens and clear-cut areas; the replacement of still existing grazing and straw-substitute collection rights with the provision of fodder, straw and paddocks if necessary; the fencing-in of livestock herds doing damage to the land and the forests; the regulation of straw-making and its restriction to locations where such practice will not harm woodlands; and many other problems. The forest laws must be complemented by regulations pertaining to the protection and care of nature. Such legal security must be extended to nature preserves and natural monuments as well as to plants and non-game animals. It is also the purpose of such conservation laws to promote the beautification of the countryside, to do aesthetic justice to the potential of natural resources and to the public good, and to remove or prevent disfigurements of nature, should the need arise. With the aid of such laws it will be possible to improve the state of the forests as well as of the countryside to the point where these will live up to German expectations. Looking back over the activities of the General Government to date, the German Forestry Commission finds that it has carried out its responsibilities in every way as fully as was possible given the prevailing conditions. The measures taken to date have been strictly temporary solutions addressing the requirements of wartime; a permanent reconstruction and development of the forestry situation will not be possible until after the end of the war.

*[Trans. note:] the peasants' entitlement to make use of the entire woodlands and their resources, without actually owning any of them. ...back... **[Trans. note:] the European polecat, not to be confused with the North American skunk, to which it is related and which is often (though incorrectly) called "polecat". ...back... ***[Trans. note:] much like an American forest ranger. ...back...

****[Trans. note:] The Todt Organization was founded in 1938 by Fritz Todt, National Socialist politician and engineer. This organization effected the construction of facilities required for the war – such as the Atlantic Wall,

U-boat (submarine) bunkers, air-raid shelters, etc., in both Germany and the occupied territories. ...back...

|