|

Politics of Food Supply

in the District of Warsaw (Part 2)

4. Regulation of Marketing Practices, and Food Distribution

Marketing regulations are of great importance in the General Government. They are intended to ensure that the foodstuffs produced get to the consumer as required, and this represents yet another area in which the General Government had to start from scratch, as the former Polish state had done nothing at all in this respect. There were no modern refining and processing plants, no storage facilities, no adequate

cold-storage depots and no canning facilities. Poland's stage of development in these matters literally lagged 100 years behind Germany's.

No food supplies worth mentioning still existed when the German administration came into effect, as everything had been consumed during the Polish Campaign and especially during the siege of Warsaw. To prevent famine, considerable quantities of grain and sugar had to be supplied from the Reich the first winter,

1939–40. This helped to get through that first winter, which on top of everything else was also bitterly cold.

These emergency measures, however, could not be a permanent solution; systematic new measures had to be introduced to ensure a uniform and consistent food supply for the people.

At first, bread and sugar were made available on a ration card system which was gradually extended to include meat, eggs, flour, and other groceries as well. The absence of any sort of

well-ordered population registry interfered no less unpleasantly with the introduction of this food ration card program than did the constant remigration of Poles from the areas incorporated into the Reich and the incessant flood of Polish refugees from what was then the Soviet sphere of interest. At that time these migrations increased the population of the city of Warsaw by several hundreds of thousands, to more than 1.5 million.

In the District as a whole, 2.3 million persons had to be fed by means of the ration card system, since – as previously mentioned – only a small percentage of the District's population is

self-sufficient.

Considering the backward state of affair which characterized the territory of the General Government as a result of the conditions which had predominated in the Polish Republic, it was not possible to adopt the German food ration card system; instead, a simplified system had to be introduced. Only certain groups of consumers could be granted support – the entire urban population, for example. Besides the urban centers, however, the

working-class residential areas near these cities as well as the industrial areas in the countryside were also eligible. A distinction was made between

non-German average consumer groups and Jewish consumer groups. Anyone employed in factories or other enterprises which work in support of German industry or the general German interests, or in such as service a public need (eg. electrical power stations, or

gas- or water-works), was provided with extra foodstuffs.

A further difference between the General Government and the Reich is that those persons entitled to support in the General Government are not supplied with every kind of grocery; rather, only certain kinds of staple foods are provided, and only in quantities corresponding to the General Government's production levels. The quantities of these food rations depend largely on the constant improvement of the produce collection measures, for which purpose completely new means and methods have been thought up and which take into consideration the Polish mentality as well as the conditions prevailing in the General Government.

Checking eggs for flaws.

Calcium vats for preserving fresh eggs.

|

There is a great difference in the General Government between the official prices of agricultural products and the official prices of supplies and requisites for land cultivation. Farmers are therefore eager to avoid turning their agricultural products over to the official collection depots and instead to sell them on the black market, where they receive considerably higher prices which in turn let them afford the more costly agricultural requisites. This fact has led to the realization that the registration and collection of agricultural produce can only be successfully carried out if the peasants are given certain quantities of supplies and requisites as premium or bonus. For this reason, the "premium coupon system" was introduced to aid in the collection of agricultural products.

Under this system a farmer is paid the official price for his agricultural products, as well as the equivalent of 20% – 25% of their value in other goods. Specific barter goods and exchange rates have been set for individual agricultural products. For the

handing-in of grain, for example, the premium consists of textiles, alcohol and petroleum. Shoes and leather are the premium for slaughter animals. Iron goods

Production facilities for clarified butter.

|

are given in return for the delivery of potatoes. Eggs are rewarded with sugar, and crops for oil production with oil and oil cake. Barter goods are used in this way in all major collection drives.

The premium coupon system has been a success in every way and will be retained in the future.

To ensure the adequate supply of staple foods, delivery quotas for grain, potatoes,

livestock, eggs, butter etc. have been imposed on all counties, communities and villages in the District. How high these quotas are varies from case to case and depends on the area of cultivable land available, as well as on average yields and on the number of livestock.

On the whole, the farmers fill their quotas most satisfactorily. In 1941 more grain had already been turned in by the end of October than in the entire year before.

Another important area for agricultural marketing regulations is the controlled channeling of agricultural products collected through processing plants, workshops, wholesalers and retailers, and on to the consumer.

An important part of the development and consolidation of marketing regulations was

the modernization or even the downright new construction of efficient processing plants such as mills, creameries, oil extraction plants, and meat, vegetable and fish canneries etc.

The creation of new storage space in the counties for some 100,000 tons of grain as well as the creation of more food storage facilities and the expansion of the

cold-storage depot in Warsaw has gone a long way towards establishing an adequate food storage network. Despite the difficulties which wartime poses

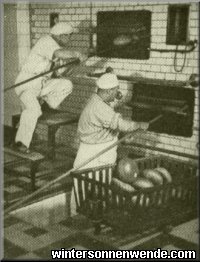

Mechanized bakery in Warsaw.

|

for the procurement of construction materials and machinery, a large part of this

build-up program has already been completed.

Beyond that, the entire bakery, cafe and butcher's trades were subjected to thorough

cleaning-up operations.

All businesses not necessary to the economy were shut down, particularly all Jewish businesses and those that were technologically poorly equipped.

In the interests of precluding any interference in the flow of goods, all Jewish involvement in the grocery trade had also been immediately eliminated. This measure was of utmost significance since previously the trade in agricultural products was almost exclusively in Jewish hands. Instead, the existing county cooperatives were turned into main collection depots in the individual county precincts, and placed under German control.

With this regulation of the marketing of agricultural products, which has been established in the General Government along completely different lines than in the Reich, and with the measures implemented towards the comprehensiveness of produce collection, it will be possible in time to achieve the General Government's

self-sufficiency in food production.

5. Co-Operatives and the Credit System

In former Poland, trade in agricultural products and requisites had been largely in Jewish hands. Conditions were particularly severe in the area of the

present-day District of Warsaw, since the Jews in the capital and its environs held the reins of society and nipped in the bud all efforts of the peasants to free themselves from their Jewish servitude by means of

self-help organizations. It was even easier to destroy Aryan trade, since the Jews also acted as financial backers and were in a position to set the prices of agricultural products at will. The buying of "standing grain" was especially lucrative; financially desperate farmers could be induced to sell their produce in spring at

give-away prices, and were deprived of their profits at

harvest-time.

When it turned out that no Aryan merchants were available after the German administration had been established and Jewish trade had been shut down, the Division of Food and Agriculture fell back on the already existing, but meagre and incomplete network of agricultural

co-operatives. Large-scale development and expansion was arranged. County precinct

co-operatives were set up in each county seat and regional

co-ops or branches of the county co-ops were established in other cities. On April 1, 1942, the District of Warsaw with its nine county precincts had 9 county

co-ops, 19 regional co-ops and 24 branch offices, with 2,500 employees altogether. German commissioners were appointed to superintend the county

co-ops. The achievement which this co-op system represents is best demonstrated by the fact that these enterprises, which had essentially been created out of nothing, could soon be put in charge of the entire agricultural trade. In 1940 the

co-ops had a turnover of 100 million zloty, and one of 130 million zloty in 1941.

The capital required was raised partly through the selling of personal shares and partly through loans from the Central

Co-Operative Bank. Vigorous advertising enabled the

co-ops to attract 59,750 members by April 1, 1942 and to raise 3,629,979 zloty through the sale of shares. Most of this money was invested. Since no suitable facilities were available for administrative headquarters or for the storage of grain and goods, changes had to be made in this respect. In 1940 and 1941, 12 gigantic silos were built and more than 50 provisional facilities were created by the renovation of existing buildings or the construction of temporary storage barns. The newly built and the temporary facilities together provide storage space for 40,000 tons of grain. The building costs involved amounted to some 10 million zloty. The government contributed a grant of 3 million zloty to this amount, and a further 3 million zloty were provided by the State Agricultural Bank in

long-term loans.

Dairy in Otwock, county precinct Warsaw (rural).

|

The dairy co-operatives developed differently. Before the war there had been

150 co-operative dairies in the area of the present District of Warsaw, but these were without exception very small enterprises. It was necessary to eliminate all those establishments which could not maintain themselves independently, or to combine these with other dairies. There are

72 co-operative dairies left in the District today, but this number will still be decreased considerably so that the more efficient enterprises may be assigned sufficiently large catchment areas. The technological state of the dairies was quite inadequate, and was greatly improved by the importing of machinery and thorough renovation of the extant facilities. It will probably not be possible to realize the planned new buildings and technological improvements before the end of the war, but until then all efforts are being made to increase the financial means of the

co-ops so that the modernization of these enterprises will be able proceed immediately as soon as the opportunity presents itself.

The existing credit co-operatives were also subjected to thorough

clean-ups. Only those institutions remain which show an adequate potential for future development. Altogether, 178 credit

co-ops with a capital of 15 million zloty still exist. The agricultural banks located in the county seats can be expanded as required in cases where the extant agricultural credit institutions are as yet inadequate.

Agricultural endeavors as well as the operations of the Division of Food and Agriculture are financed primarily by two banks. The State Agricultural Bank directly finances large landholdings; the Central

Co-Operative Bank works through local credit institutions to provide farmers with loans while providing direct financing to

co-operatives.

All co-ops are monitored and supervised by the District branch of the General Government's

Co-Op Audit Board. The District branch of the Agricultural Head Office acts as central goods exchange, supplies the trade

co-ops with the items they require, and receives all products collected by them.

Warsaw Under German Rule

Warsaw Under German Rule

German Reconstruction and Development in the District of Warsaw

|

|