|

Spatial Overview of Warsaw District

Area, Population Density, Location, Economic Structure and Landscape

When the General Government was established the region was divided into four districts, which were named for the General Government's largest cities – Cracow, Lublin, Radom and Warsaw. In 1941, at the beginning of the Russian Campaign, the District of Galicia was added; its district capital is Lemberg. The General Government's jurisdiction extends over some 144,000 sq.km. in total, an area greater than that of Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden, Thuringia and Saxony put together. The population totals some 18 million inhabitants.

Compared to the other districts, Warsaw has a special status in several respects.

In terms of area this district is the smallest. While the areas of the individual districts are not yet precisely determined, as no survey has yet been done, the following are rough estimates based on the extent of the overall territory:

| District of Cracow |

approx. |

29,700 |

sq. km. |

| District of Lublin |

" |

26,600 |

" |

| District of Radom |

" |

24,500 |

" |

| District of Warsaw |

" |

17,000 |

" |

| District of Galicia |

" |

50,000 |

" |

However, Warsaw is the most densely populated of the districts. In terms of population, precise figures are also not yet available since the General Government has not yet

taken a census, but based on available estimates the following population can

be assumed:

| District of Cracow |

approx. |

3.6 |

million |

inhabitants |

| District of Lublin |

" |

2.4 |

" |

" |

| District of Radom |

" |

3.0 |

" |

" |

| District of Warsaw |

" |

3.4 |

" |

" |

| District of Galicia |

" |

5.5 |

" |

" |

If one converts these numbers to a per-sq.-km. measure, one finds that in terms of population density, the District of Warsaw is by far the most densely populated: with 185 inhabitants per sq.km, it greatly exceeds the General Government's average population density of 128/sq.km, not to mention that of the District of Lublin, which has only 80 persons per sq.km. The unusually high population density of the District of Warsaw is due to the fact that the very large city of Warsaw falls within its boundaries.

In terms of location, Warsaw is the General Government's northernmost district; it is an elongated stretch of land extending from west to east and is bordered in the west by the Warthegau,* in the north by the province of East Prussia (which has been expanded to include the county of Zichenau), in the east by the region of Bialystok (with the River Bug making up the main part of the border), and in the south by the General Government's districts of Lublin and Radom. The Vistula, on whose banks the District capital Warsaw is located, courses in a gentle arc from the south to the

north-west and bisects the District into a western and an eastern half.

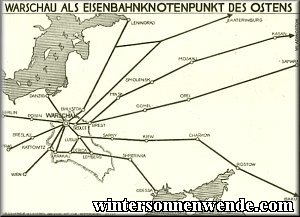

The Warsaw Basin, which is also the location of the city of Warsaw, constitutes the focus of the District's transportation and economic network. All of the District's major traffic arteries come together here. Main traffic routes run from west to east, reflecting the shape of the District. Railroads and highways thus connect Warsaw with Berlin via Posen, Kutno, Lowitsch and Sochaczew, with Breslau via Litzmannstadt [now Lodz], and with the Upper Silesian coal mines via Tschenstochau [now Czestochowa] and Petrikau. Rail and highway connections

continue towards the East: to Bialystok and Minsk via Malkinia and Ostrow, and on to Moscow; to

Brest-Litowsk and Pinsk via Siedlce, as well as to Wolhynia and Galicia via Garwolin and Lublin. The waterway of the Vistula as well as a

north–south rail line provide connections with Danzig [now Gdansk] in the north and Cracow in the south.

Due to this convenient transport situation, which can be further augmented by highways and by the canalization of the River Bug and its connection with the Russian canal system, Warsaw is a traffic junction and economic center of great importance.1

In accordance with the physical setting, the Warsaw Basin harbors various industries which bear mention and which also extend into those of the District's western regions so convenient for purposes of transportation. West of Warsaw, for example, there is an electric power station and a railway repair plant in Pruzskow; the General Government's largest paper mill is in Jeziorna; further, there are several large

metal-processing plants ("Zyrardower Manufacturing Inc.") in Zyrardow, as well as a

spun-rayon factory in Chodakow near Sochaczew and a brass rolling mill in Glowno.

In other regards the District of Warsaw is predominantly agricultural in nature. The terrain is generally flat and even, and gently rolling in but a few regions. The fertility of the soil, which is sandy in some places, clay in others, and occasionally even slightly boggy, ranges from fair to good. Principal crops are rye, potatoes and oats; sugar beets do especially well in the western areas; however, the soil is less suitable for wheat. Agricultural ponds are well developed everywhere, and particularly so on the large estates. Horticulture has improved significantly in the vicinity of the city of Warsaw, but suffered considerable setbacks through the extraordinarily severe past few winters. Various larger estates are sizeable stud farms, where a Polish

cross-breed horse is being bred.

In general, the District is only sparsely forested, forestry being of significance only in the eastern regions where some larger areas are up to

one-third woodland.2 In earlier days, hunting, practised by the Russian or Polish high nobility, must also have been of significance there. In Skierniewice the Russian Czar Nicholas II had a hunting lodge where the Conference of the Three Emperors took place in 1884 between the Emperors of Germany, Austria and Russia.

Agriculture and forestry were the prerequisites for the various commercial or industrial processing works which are scattered throughout the District, including several sugar refineries, leather works, sawmills, woodworking plants, a match factory in Blonie and a wood products impregnation plant in Ostrow.

Whereas the German countryside is characterized by a harmonious interrelationship between the cities and the countryside, such an interrelationship is only partially the case in the area of the former Polish nation. While there are

Typical Polish farmstead.

|

a number of

medium-sized cities with populations from 10,000 to 25,000, these are more distant from each other than

similarly-sized cities in the Reich. Such cities thus serve more as central trade supply points than comparable German cities, but they are most inadequately equipped for the purpose. The very layout and urban development of these cities is usually such that at best they can be compared to small towns in the Reich, with no more than 5,000 inhabitants.

Stone is the most common building material in the western part of the District, but simple lumber construction predominates in the east. The stores and workshops in these towns are downright primitive. Bright, spacious and clean stores such as we are accustomed to seeing in

medium-sized towns in the Reich are not to be found in the District's towns of comparable size.

"Modern" Polish school building.

|

City development has been unsystematic and discordant. Right beside low, primitive wooden huts one can find unfinished

three-story brick buildings in ostentatiously "modern" style; schools of pretentious architectural conception are juxtaposed with dirty little cottages; next to detached houses with their own gardens one sees tenements with sprawling,

poor-quality additions in which countless families live crowded tightly together. Wooden backyard shacks, which in Germany would be considered stables at best,

Polish farmstead.

|

are here dwellings for people; basement rooms and poorly constructed attics also serve as living quarters.

Aside from some few thoroughfares, the city streets with their uneven cobblestone paving are uniformly poorly maintained. Few towns have plumbing, and sewer systems are next to nonexistent. Until German administration brought order to this chaos, refuse and sewage were simply piped into the streets.

Chopin House in Sochaczew.

|

Some of the provincial towns are quite impressively old. The cities of Sochaczew and Lowitsch, for example, received their town charters in the same century as Warsaw. Sochaczew was the seat of the Dukes of Mazovia; a relic from those times – the ruin of their castle – still stands on the high bank of the River Bzura. In earlier days, Lowitsch was the seat of the archbishops of Gnesen [now Gniezno]. Some larger buildings, as well as the ruins of the diocesan castle which the Russians had destroyed, still bear witness to this city's former significance. Various buildings in the town of Siedlce – the diocesan town to this day – also reveal the importance conferred on this town by the presence of the Church. But nothing approaching the significance of cultural centers shaped by centuries of tradition, such as is the case with many an ancient German town of middle size, is to be found in the Polish provincial towns of the District, and in fact it is precisely these

medium-sized towns which reveal the vast gulf which separates the cultural level of this region and that of the Reich.

Market Square in Siedlce.

|

The focal point of a medium-sized Polish town is usually a

cobble-stoned market square where, once or twice a week, on market days, a bustle of trade and business dominates the scene. Where the Jews have disappeared from the city scene and the peasants come to market attired in their colorful national dress, a visitor is greeted by a picturesque and lively townscape.

The smaller towns of about 5,000 inhabitants are for the most part dreary places and fall far short of the standard of even the most unassuming small German merchant towns.

Away from the main traffic arteries, the flat countryside can only be reached via unimproved roads which often turn into trails of deep mud in spring and autumn. The "ribbon settlement" system is predominant:

View of a Polish village.

|

almost all villages lie along one long street, so that a single town is frequently 4 to 5 km. long. Residential buildings, stables and barns – all arranged around the perimeter of a rectangular yard,

single-storied and constructed largely of

wood – generally bear roofs of reed, straw or roofing felt. The town road and the yards are lined with trees, mostly poplars, which shelter the town from the wind and obscure it almost totally when the scene is viewed from a distance. Polish villages tend to look as though they were cowering timidly close to the ground, seeking shelter from the rigors of the weather and the intimidating,

wide-open spaces surrounding them.

Being of Eastern race, the Polish peasant has no great energies for expansive action, but rather the desire to spend his life in a modest, merely adequate existence.

The primitive accommodations

of the Polish rural populace.

|

He is not the originator of profound and panoramic ideas; content to live in a stupor, he takes little notice of time and space, and has shaped his settlements and countryside accordingly. Everything bears an aura of the coincidental; there is no sense of

well-planned order, of ambitious configuration such as is to be found everywhere in our Reich, no sense of any responsible planning for the future, or even of any activity extending beyond the limits of the town at all. If the Polish interim empire had achieved any significant developmental prerequisites at all desirable for European cultural conditions, these developments were only possible because the Polish intelligentsia had imitated central and western European examples. There are next to no original creative achievements. An observer will thus notice the contrast, so evident in the Polish scene, between the ancient, simple Polish condition of inertia, and the artificially introduced modern development. For example, a primitive Polish village may exhibit a modern

flat-design school house, or one of the bottomless Polish village streets may suddenly be crossed by a modern asphalt highway. The sum of it all produces an effect of artificiality. There is a complete absence of

large-scale planning, which would also be the necessary foundation for any development of the countryside.

Similarly, the middle- and large-sized estates scattered throughout the countryside as a rule do not give the impression of being sites of any particular cultural niveau. Their owners – occasionally they are nobles with considerable land holdings – have only rarely managed to turn their manor houses into comfortable country seats. Rather, most of them are poorly constructed, in a state of disrepair, and not fit for German inhabitants without first being thoroughly cleaned and renovated. The few exceptions – namely country seats of the ancient Polish high aristocracy, which in earlier days had often had the benefit of German education or military

training – only serve to prove the rule.

The Catholic Church exerts a particularly strong influence on the people, especially on the peasants. Large, roomy churches are conspicuous throughout the country, and their location has often been chosen in such a way that they form a hub for the main roads linking the Polish cities. A good number of towns are affiliated with each church. The municipal government buildings in all their inadequacy often appear downright pathetic next to the imposing churches.

Traditional costumes of Lowitsch.

|

On Sundays and holidays, the rural people don their best holiday dress and travel to church on foot or by

horse-drawn "panje" cart. In areas where traditional dress is worn, the women and girls put on their colorful costumes; they walk barefoot and carry their shoes in their hands, to put them on only just before entering the church. The main entranceways to the towns are marked by tall wooden crosses, which no peasant passes without taking off his hat and crossing himself. When the parish priest is called to a sickbed or ventures on some other errand of mercy, the

passers-by kneel in greeting and make the sign of the cross.

Sprinkled throughout the Polish countryside are the occasional villages which were founded by Germans and are even today populated partly by Germans. Even if the District's

Farmhouse in an ethnic German settlement in Poland.

|

German settlements bear no comparison with German farming villages in the settlers' Swabian or North German homeland, they do differ in their layout and general outward appearance from most Polish villages. Their residential buildings, often made of stone or unfired clay bricks, contain more living space than the houses of the Polish. They are kept considerably cleaner and more comfortably furnished. Also, the German peasants' farms are not as closely crowded together as those of the Polish. Every now and then, one can still find on a German estate the grapevine which the first settlers brought with them from their homeland.

As a rule, the German peasants have retained their national traditions and their German character quite well. They are fully aware of their mostly Swabian origins, and some of them are still proficient in the Swabian dialect. There are many children and elderly among them who can barely make sense of the Polish language.

At the time of their founding, the German towns were usually given German names, which the Polish later Polonized or changed outright. Today the peasants again use the beautiful old German names for their home towns – for example,

Alt-Ilvesheim, Ludwigsburg, Schwiningen, Mathildendorf, Karlshof, Frankenfeld, Königsdorf, Erdmannsweiler.

All in all, the District in its variety and diversity has much to offer that is interesting. It is not yet by nature a uniformly ordered spatial construct in the German sense. Such reorganization will take decades.

*[Trans. note:] a "Gau" was a large administrative district of the German Reich....back...

1Cf. Section V.I.: "The District of Warsaw as Commercial and Industrial Center of the General Government". ...back...

2Cf. Section VII.: "Forestry and the Timber Industry". ...back...

Warsaw Under German Rule

Warsaw Under German Rule

German Reconstruction and Development in the District of Warsaw

|

|