|

Marching Into Warsaw, and the Führer-Parade In the early morning of October 1, 1939, the German troops assembled in full marching order, ready to move into Warsaw.1 That historic day on which Poland's fate was sealed was unspeakably memorable. The first striking experience of the day was meeting the last of the Polish army moving out of the city; the Polish garrison forces had begun their march into captivity two days ago. German news reels and illustrated papers have often shown this event, which was repeated in the course of the war on other battle sites as well but which was a first when it happened then in the capital of the former Republic of Poland. It was an unforgettable sight: on the one side, the Wehrmacht regiments in full marching order, as well as the SS and police formations, none of whom any longer showed even a sign of the strains of the campaign just past, and on the other, the disarmed remainder of the defeated Polish army, facing captivity tired and worn out. This immense contrast was best reflected in the faces of the troops as they marched past each other: the Germans radiant with joy at the victory they had earned, the Poles utterly despondent at their defeat. One might have expected the German troops to accompany their move into Warsaw with military marching music and joyful songs. But this was not at all the case. For as long as the defeated Polish army passed by us, no marches or songs were to be heard; the march-past took place silently, and was all the more impressive for it. It was not until the last Polish troops had passed the demarcation line that the German military marches rang out for the first time, and then Warsaw's streets echoed not only with the resounding steps of the German columns but also with the singing of German soldiers' tunes, in a way that Warsaw had not seen since the first world war.

We had passed the days preceding the surrender in the vicinity of Warsaw, and had seen the mighty pillars of fire and the clouds of smoke that had hung over the city, but we had not believed that a city with over a million inhabitants could be devastated to such a degree in such a short time. At one of the great art exhibitions in Munich some time later, a painting was displayed which bore the title "The March Into Warsaw". It showed a German company moving into the burning city along ruins and devastated rows of houses. What an artist had depicted in this painting was true to life: the German troops had indeed moved in along rows of ruins. Entire city districts were uniform expanses of rubble. Fires still smoldered in houses everywhere. Wreckage from collapsed buildings often spread right into the middle of the streets, where some of the streetcars still stood which the Poles in their senseless mania of resistance had turned into barricades. Dead horses lay

All in all, Warsaw at that time looked like a completely destroyed city, doomed to extinction.

But amongst these ruins – and that was the third striking experience of that day –, along the streets on which the Wehrmacht was moving in, thousands of Jews were standing, watching curiously, some even smiling. In the previous course of the Polish Campaign, we had already noticed in smaller cities how great the Jewish part of the population was in Poland, but we had never before seen such an absolute throng of Jews at one time as we saw that day in Warsaw. And on top of that, the majority of them were of that type which most of us had only ever seen in pictures and caricatures: typical Eastern European Jews with long flowing beards and wearing caftans and yarmulkes. That was when it first dawned on us what a difficult problem would need to be solved here; there were at that time more than half a million Jews in Warsaw, which made it the city with proportionally the greatest Jewish population in all of Europe – and it was perfectly clear to us that these many thousands of Jews would have to be segregated from the rest of the populace, and particularly from us Germans. In the evening, when we took up our accommodations in the building of the former Supreme Court on Krasinski Square, we looked out the shattered windows of this building, whose gable frieze had been created by none less than Andreas Schlüter, at the houses lying opposite, which had been destroyed completely and among whose ruins the occasional fire still flickered. In one corner of the Square, the silhouette of a memorial statue was clearly visible, of a man with arm upraised, clutching a curved sword and attacking the enemy. This statue was to preserve the memory of the Polish shoemaker Kilinski, a freedom-fighter of the last century who had fought against the Russians. As we thoughtfully regarded this monument of the revolution, we took it as a reminder that the military victory we had achieved did not yet mean the end of the battle. An observer standing in Krasinski Square today will find no more traces of this destruction. The damaged houses have been removed right down to the last brick, resulting in a much larger Square than before, which sets the beautiful building of Krasinski Palace off to particular advantage. The Kilinski Monument has also disappeared. It was removed as reprisal against the vandalism perpetrated by Polish villains on the Thorwaldsen Monument, which had been erected in honor of the great German astronomer Nikolaus Copernicus.

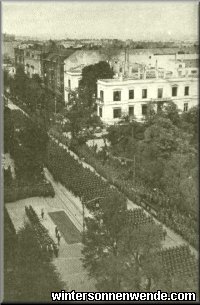

Surrounded by his Generals and the leading men of the Party, Adolf Hitler arrived in Poland's former capital on October 6, 1939. He drove past the Poniatowski Monument in what was then Pilsudski Square, where the former General Staff building stood in which Polish Field Marshal Rydz-Smigli had resided up until the time of his ignominious escape. Then, on Ujazdowski Avenue, the Führer took the salute at the march-past.

And then, for more than two hours, the battle-uniformed German troops marched past their Führer and Supreme Commander. The German military marches ring out jubilantly, and with a firm step the soldiers whose young faces have hardened in battle pass by the Führer. Their eyes shine with joy and pride. Time and again the Führer salutes the passing troops, among which there is many a soldier who wears the Iron Cross as sign of bravery. Some of them, for the first time ever, also wear a bar with the Iron Cross, as sign that they have done their duty in this war as they did it in the first, great World War of 1914-1918. After the march-past the Führer visited Belvedere Castle, where Pilsudski had lived. Then he left for the airfield, to give a full account of the Polish Campaign in the Reichstag the next day. All those who were so fortunate as to be able to witness that parade gained the unshakeable conviction that such an army, which only a few days after hard and bloody battle was able to

The Führer's historic visit, and the mighty parade of the Wehrmacht, have been commemorated in Warsaw: on the first anniversary of the parade, during a traditional parade before Field Marshal List, Governor-General Dr. Frank renamed Ujazdowski Avenue "Victory Avenue". The city's largest and most beautiful square, however, was renamed "Adolf Hitler Square".

1The author of this book was a member of one unit that had assembled on the highroad between Okecie and Warsaw, and from there participated in the

march-in. ...back...

|